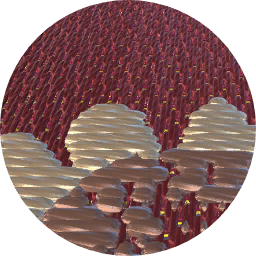

Description

Direct and dramatic, this bronze half-length statue represents a nude woman, aquatic from the waist down, who holds a scaly tail in each hand. Her long hair trails behind her to a set of fish gills that fan out from all sides of her body. She wears a pointed crown, which is clearly a later addition, though her roughened pate and open cranium indicate the presence of a previous crown. She would have been placed high so that the viewer could not see the top of her head. There is no physical evidence that this bronze was part of a fountain; rather, it appears to be an emblematic decoration.[1]The statue reflects traditional types of mermaid figures and in particular the mythic Greek sirens. The sculptured figure of a woman holding her own fish tails can be found on Romanesque capitals, and in the sixteenth century the image became a decorative motif for tapestries and small bronze candelabra.[2] The crown, however, indicates that this statue is a specific dynastic symbol. A great Roman family, the Colonna — and especially the princely Paliano branch — adopted this image as an emblem. As such, it appeared on their tombs in Rome, at San Giovanni in Laterano, and in the town of Paliano, as well as on furniture and in ceiling decorations.[3] A volume of personal and family devices (imprese) collected by Paolo Giovio illustrates and describes the emblem of Stefano Colonna and quotes his motto, "Contemnit tuta procellas" (She defies the tempests).[4] The most illustrious member of the family, Marcantonio Colonna (1535 – 1584), was celebrated for defeating the Turks at the battle of Lepanto in 1571.[5] A siren appears on his armor in a painting and tops two rostral columns on a stone relief memorializing the victory at Lepanto.[6] It would be particularly appropriate if, as in the stone memorial, the bronze Siren had originally been displayed on top of a column, since a cylindrical shaft was also a family emblem (colonna is Italian for column). Her gills would have spread down around it. The brusque chasing of her hair and some other features would be explained if the figure was meant to be seen from a distance — for example, from a perch atop a column. A 1644 inventory mentions "a siren of bronze, with a crown on her head" standing in a small room in the Palazzo Barberini apartments of Cardinal Antonio Barberini.[7] Antonio’s brother Taddeo was the husband of Princess Anna Colonna, and until recently it seemed to be a foregone conclusion that Antonio had received the Siren from Taddeo. Archival research, however, has turned up an inventory of April 1627 that documents the sculpture as in the palace of the recently deceased Cardinal Francesco Maria del Monte on the via di Ripetta.[8] Peter Bell has pointed out that it could have been purchased by Antonio Barberini directly from Del Monte’s heirs.[9] Thus, there is no proof that the Siren was owned by the Colonnas. Nonetheless its iconography points to them as the family most likely to have commissioned the Museum’s imposing and doubtless expensive bronze; moreover, it is not out of line to guess that it was one of many works created to celebrate the great victory of Marcantonio Colonna in 1571 and that it remained among the family’s possessions for some time. It is difficult to attribute the Siren directly to any artist, but its style is close to Roman bronze work of the period 1570 – 90. Museum curator Olga Raggio noted that Taddeo Landini’s bronze youths of 1581 – 84 on the Fontana delle Tartarughe in Rome, for example, have similar rhythmical poses and wet-looking, tousled hair.[10] Another comparison, one that James Draper has informally proposed, is with the bronze lions supporting the Vatican obelisk that Lodovico del Duca cast in 1586, after models by Prospero Antichi and Francesco da Pietrasanta (Saint Peter’s Square, Rome). The vigorous modeling of the lions’ manes was meant to be seen from afar, as was the Siren’s hair, and the statues have similar iconic roles as bronze decorations. Like the Vatican lions, the Siren was likely a collaboration between sculptor and bronze founder, who created a brilliant — essentially Roman — emblem.[Ian Wardropper. European Sculpture, 1400–1900, In the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York, 2011, no. 28, pp. 90–92.]Footnotes:[1] A technical examination by Richard E. Stone on December 10, 1999 (report in the curatorial files of the Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts, Metropolitan Museum) showed that it has no residual deposit of silt or unfired clay that would point to its use as a fountain; the crown has an artificial patination and is clumsily worked, unlike the body of the figure.[2] A twelfth-century capital at the church of Saint-Maurice, Saint-Dié (Vosges), and a capital from the end of the twelfth century at the cathedral of Notre-Dame, Le Puy (Haute-Loire), are illustrated in Jacqueline Leclercq-Marx. La Sirène dans la pensée et dans l’art de l’Antiquité et du Moyen-Âge: Du mythe païen au symbole chrétien. Publication de la Classe des Beaux-Arts, collection in-4, ser. 3, vol. 2. Brussels, 1997, p. 135, ill. no. 72, p. 147, ill. no. 87. There are two bronze Mermaids in the Museum’s collection (Padua, first half of the sixteenth century, H. 5 in. [12.7 cm], acc. nos. 32.100.174 and 32.100.175).[3] Ermete Rossi. "Le statue di Alessandro Farnese e Marcantonio Colonna in Campidoglio." Archivio della Società Romana di Storia Patria 51 (1928), pp. 15–32, pp. 19 – 20.[4] Paolo Giovio. Dialogo dell’imprese military et amorose. Lyons, 1574. [Reprint ed., Dialogo dell’imprese. Philosophy of Images 6. New York, 1979.], p. 149.[5] The triumphal procession in Rome given in his honor after the victory by Pope Pius V and statues erected to him are described in E. Rossi 1928, pp. 19 – 32.[6] Alberto di Castro, Paola Peccolo, and Valentina Gazzaniga. Marmorari e argentieri a Roma e nel Lazio tra Cinquecento e Seicento: I committenti, i documenti, le opera. Universo barocco. Rome, 1994, p. 321, fig. 100. [7] Marilyn Aronberg Lavin. Seventeenth-Century Barberini Documents and Inventories of Art. New York, 1975, p. 178 (iv, inv. 44, no. 577).[8] Archivio di Stato, Rome, 30 Notai Capitolini, Paulus Vespignanus, ufficio 28, vol. 138, fols. 574r – 588v (entries published in Christoph Luitpold Frommel. "Caravaggios Frühwerk und der Kardinal Francesco Maria del Monte." Storia dell’arte, nos. 9–10 (1971), pp. 5–52, Appendix, pp. 30 – 49). Lucia Faedo (Lucia Faedo. "Girolamo Tezi e il suo edificio di parole." In Aedes Barberinae ad Quirinalem descriptae / Descrizione di Palazzo Barberini al Quirinale: Il palazzo, gli affreschi, le collezioni, la corte, edited by Lucia Faedo and Thomas Frangenberg, pp. 3–117. Pisa, 2005, pp. 50 – 55) connected the bronze Siren in the Palazzo del Monte with the one in the Palazzo Barberini, but she did not know of the existence of the Museum’s sculpture.[9] Peter Bell was the first to identify the Del Monte – Barberini bronze as the New York Siren; see Bell forthcoming.[10] Raggio in "Recent Acquisitions: A Selection, 1999–2000." Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, n.s., 58, no. 2 (Autumn 2000), p. 24.