Description

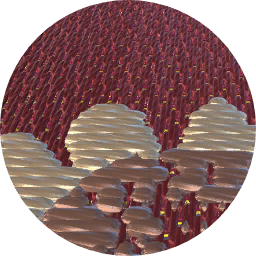

In the half-human, half-animal features of the mythical race of satyrs, Andrea Briosco, called Riccio, found great expressive potential. Furthermore, the creatures’ classical associations appealed to the sculptor’s learned clientele, who purchased the bronze statuettes that were his preferred medium. These diminutive objects could also be made into useful desktop equipment for writing or lighting by placing containers for ink, sand, or oil in the satyrs’ arms. A hole in the shell shouldered by the Museum’s figure may have held a chain to tether a snuffer for candles stuck on the lamp’s pricket, while the gadrooned vase under his right arm would have contained ink. Although it seems almost oversize for its purpose, the statuette was nevertheless a practical object: the lamp was raised high enough to cast a wide light, and the ink was proffered at a reasonable level to dip in a quill. In 1985 Dieter Blume made the interesting proposal, now generally accepted, that this figure, which had long been identified as a satyr, in fact represents Pan, the Greek deity with legs and horns of a goat, whose power over nature could sow panic or stir creation.[1] The flaming oil and ink thus must symbolize both his sway over the elements and the inspiration sought by any scholar who read and wrote with their aid. While functional, it is above all a powerful sculpture. Against the limited group of autograph works by Riccio in this category and the extensive number of workshop productions, this one stands out on account of its large size and forceful presence. Its model is a well-known pair of lifesize antique marble satyr-atlantes once in the Della Valle collection in Rome and today in the Musei Capitolini in that city.[2] Denise Allen is of the opinion that drawings of those ancient satyrs by artists such as Bernardino da Parenzo may have been the sculptor’s actual source.[3] She points out that their upraised arms and the baskets on their heads have been adapted to this small sculpture’s pose and function but that the tensile strength of the metal has been exploited here to widen the creature’s stance into a dynamic stride. Specific features borrowed from the Della Valle satyrs, such as the closely spaced horns, the ram’s skin strapped over the shoulder, and the heavily muscled torso, reveal that Riccio paid close attention to the source.While there is no question that this is a masterful Renaissance bronze, its attribution to Riccio and its date have been debated. The pioneer of Renaissance bronze studies, Wilhelm von Bode, was the first to propose Riccio as the artist, and his opinion was enthusiastically seconded by the foremost expert on North Italian bronzes, Leo Planiscig.[4] Some scholars have recently returned to the question of authorship, noting some anomalies in the statuette’s physical characteristics, particularly the pronounced musculature of the torso and the relatively wide waist. For example, Denise Allen, who finds that the closest comparison for the treatment of the torso is the nude beggar in Riccio’s Saint Martin relief (Galleria Giorgio Fraschetti alla Ca’ d’Oro, Venice; probably after 1513), observes that the beggar’s waist is narrower and his chest smoother than Pan’s.[5] Its closest counterpart, she notes, is the Seated Satyr with a Conch Shell in the Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence, which also has an animal skin strapped to the chest and holds similar (though not identical) objects, which, like Pan’s shell and vase, were chosen from a stock of models used in accepted works by Riccio. But the Seated Satyr is sometimes attributed to a sculptor in Riccio’s workshop and dated to the 1520s, which raises questions about the Metropolitan Museum’s bronze. Many features do favor Riccio’s authorship. The striding pose is also found in the artist’s Warrior and Strigil Bearer (both are in private collections);[6] in fact, Riccio demonstrated an interest in testing to the limit the balance of many of his sculptures, and this example is no exception. Richard E. Stone has identified technical qualities that keep Pan within the boundaries of Riccio’s working manner. [7] He notes that the composition of the bronze used here and in the Strigil Bearer and Shouting Horseman (Victoria and Albert Museum, London) is characterized by a medium tin content, light leading, and the same pattern of minor trace elements; moreover, the core pins of all three are very thin. James Draper originally placed Pan early in Riccio’s career, about 1507 – 10; however, as Allen proposes, the statuette’s forceful stance and musculature may be better explained as the product of his mature style. Perhaps Riccio adjusted his later style to suit a particular client, as Nicholas Penny wondered.[8][Ian Wardropper. European Sculpture, 1400–1900, In the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York, 2011, no. 15, pp. 54–55.]Footnotes: [1] Dieter Blume. "Beseelte Natur und ländliche Idylle." In Natur und Antike in der Renaissance, pp. 173–97. Exh. cat. Liebieghaus, Frankfurt am Main; 1985–86. Frankfurt, 1985, pp. 184 – 85.[2] Francis Haskell and Nicholas Penny. Taste and the Antique: The Lure of Classical Sculpture, 1500–1900. New Haven, 1981, pp. 301 – 3, no. 75, figs. 158, 159.[3] Denise Allen in Andrea Riccio: Renaissance Master of Bronze. Exh. cat. by Denise Allen, with Peta Motture et al. Frick Collection, New York; 2008–9. New York and London, 2008, p. 149, fig. 8.2.[4] Wilhelm von Bode. Die italienischen Bronzestatuetten der Renaissance. 3 vols. Berlin, 1907–12. [Vols. 1 and 2 published 1907.], vol. 3, pp. 22, 29, pl. ccxliii; Planiscig 1927, pp. 346 – 47, 484, no. 116, fig. 417.[5] Allen in Riccio 2008, p. 147.[6] Warrior is in a private collection in the United Kingdom; Strigil Bearer is in the collection of Mr. and Mrs. J. Tomilson Hill, New York. [7] Richard E. Stone. "Riccio: Technology and Connoisseurship." In Riccio 2008, pp. 81–96, pp. 88 – 90.[8] Nicholas Penny. "Andrea Riccio: New York." [Review of the exhibition "Andrea Riccio: Renaissance Master of Bronze," at the Frick Collection, New York, and the accompanying publication.] Burlington Magazine 151 (January 2009), pp. 64–65, p. 65.