Description

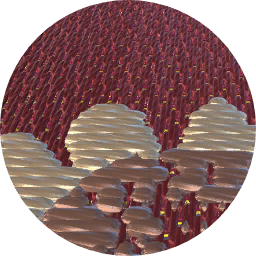

The great master of the small bronze in the early Renaissance, Andrea Briosco, called Riccio, trained first as a goldsmith in the workshop of his father, Ambrogio Briosco. He owes his renown to the bronze statuettes and functional objects he cast for a small circle of clients, particularly in his native Padua. Many of them were made in homage to the art of antiquity; Riccio borrowed motifs from ancient sources and combined them in novel ways to give them fresh meaning for his humanist patrons in that university town. Although members of his workshop and his followers issued, on a level of mass production, bronze oil lamps as well as inkwells and candlesticks, Riccio himself produced only a handful of them, including some unique oil lamps, which transcend utility to become masterpieces. Long in the collection of the Rothschild family, this is one of three superlative examples of its kind; the others are the Morgan Lamp, in the Frick Collection, New York, and the Cadogan Lamp, in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. The three share many motifs, but with a fertile imagination Riccio incorporated them into each lamp in such a way that they seem to be in a constant state of flux, changing their guise from one object to the other before our eyes. While its owners may have prized it too highly to use it for lighting, this is a functioning oil lamp. The hinged lid opens by means of the handle topped with a grotesque head — its upward movement limited by the ram’s head spiraling behind — and reveals two connecting reservoirs for oil. When the lid is closed, the grotesque head appears to be blowing on a wick that rose from a tongue protruding from the opening below. Curling tendrils above and below serve to suspend the lamp from hooks or to support it as struts on a table. Overall, the lamp takes the form of a fanciful ancient ship or galley. Its prow is like a nautical battering ram; the Cadogan Lamp has a spike that refers to this function and a proper poop deck behind.[1] By curling the spike into a continuous element with two loops, Riccio found a more elegant solution for the Museum’s lamp. The tendrils buoy up the body of the lamp, lending lightness and a sense of mobility to the otherwise dense bronze mass. Of the three superb lamps mentioned here, this is the only complete example, and it demonstrates how lid, handles, and loops were intended to work.On the lid a pair of putti perch, embracing swanlike creatures that emerge from the swelling bronze surface and tuck their necks back into it. The Cadogan Lamp lid supports a single putto astride a dolphin that swims in the opposite direction from the boat; a hole in the poop may indicate where a second figure once stood, possibly the helmsman, as Anthony Radcliffe hypothesized.[2] An engraving of the Morgan Lamp, made in 1652, when it was already missing its lid, shows a lyre-playing putto seated against the rear handle; the remains of a foot on the forward lip suggest that another putto stood facing the wick.[3] Therefore, all of the lamps originally had figures of children riding on top. The Morgan Lamp is in the shape of a classical boot, not a ship. But these fantastic objects were not meant to be taken literally: they make reference to ancient prototypes of lamps,[4] and with their riding figures they also suggest both the richly decorated floats that Renaissance artists created for triumphal processions and illustrations of such elaborate chariots in works like Francesco Colonna’s Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (1499).Encrusted with shells, bucrania, harpies, garlands, and other classical decorative motifs, the body of each lamp is also decorated with friezes of putti. The Museum’s lamp displays a dozen in the relief on one side and eleven on the other. In the first, the twelve naked children dance, play with a ram, step over an ewer, and blow on a horn; in the second, some dance, one plays a pipe on the far right, and a kneeling group sit in a circle around a ram at the left. These friezes become narrower at one end, and as they taper, each child remains clearly delineated, but the poses shift from upright to crouching to seated.The three lamps are closely related to Riccio’s most substantial work in bronze, the Paschal candlestick in the basilica of San Antonio (Il Santo) in Padua, since similar motifs are present on all. He began the colossal liturgical object in 1507, was apparently interrupted in 1509, and completed it only in 1516. Although the dating of the various parts of the candlestick is conjectural, most scholars place the three lamps within the period of its making or shortly afterward.[Ian Wardropper. European Sculpture, 1400–1900, In the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York, 2011, no. 14, pp. 50–53.]Footnotes:[1] Anthony Radcliffe. "Bronze Oil Lamps by Riccio." Yearbook (Victoria and Albert Museum), no. 3 (1972), pp. 29–58, pp. 29 – 35, provides the most complete description of the Cadogan Lamp as well as the most comprehensive analysis of all the known lamps by Riccio. Peta Motture’s account in Andrea Riccio: Renaissance Master of Bronze. Exh. cat. by Denise Allen, with Peta Motture et al. Frick Collection, New York; 2008–9. New York and London, 2008, pp. 174 – 81, no. 13, is the most recent.[2] Radcliffe 1972, p. 31.[3] Fortunius Licetus. De Lucernis antiquorum reconditis libb. sex. Udine, 1652; Radcliffe 1972, fig. 30.[4] Motture (in Riccio 2008, p. 181) points to an ancient lamp in Lyons as a prototype.