Description

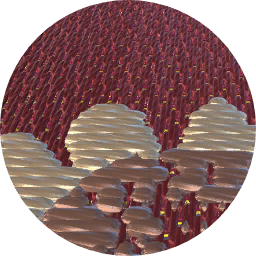

The years between 1815 and 1848 in Germany and Austria were characterized by a conservative political and cultural climate. The period and its style of interior decoration are both called Biedermeier, after a fictional character invented by the poet Ludwig Eichrodt (1827–1892) in the 1850s. Although the term invokes qualities typical of the German bourgeoisie (unpretentiousness, thrift, domesticity), the origin of the Biedermeier furniture style was totally aristocratic. The simple, elegant forms with their clean lines and light-colored wood veneer derived from the ornamentally restrained furniture that had been made for the royal and princely households of Germany, Austria, and France beginning in the late eighteenth century.[1] For this market, even Parisian ébénistes, such as Canabas, Saunier, Jacob, and Molitor,[2] produced simple mahogany pieces that were set apart only by their excellent materials and outstanding craftsmanship.[3] Berlin, Munich, and Viennese cabinetmakers followed suit, creating similar, refined furniture.[4]Contemporary watercolors document that Biedermeier interiors were characterized by the use of strong colors for paint, wallpaper, and fabrics.[5] Consequently, the upholstery specialist of the Metropolitan Museum's Objects Conservation Department was delighted but not surprised to discover some silk threads of a strong aquamarine color beneath the former show covers on the present chair and its pair, which is also in the Museum's collection.[6] An appropriate fabric was acquired and dyed to match these remnants of the earliest upholstery. Seldom are curators and conservators given such a splendid opportunity to recreate the original appearance of a piece of furniture and to do it with the correct material, in this case, precious silk. The spring upholstery on the drop-on seats is original, as are large parts of the surface finish.[7] The quest for truly comfortable seating furniture characterized the Biedermeier period: in 1822 Georg Junigl obtained a patent in Vienna "for his improvement on contemporary methods of furniture upholstery which, by means of a special preparation of hemp and with the assistance of iron springs, he renders so elastic that it is not inferior to horsehair upholstery."[8]The Museum's side chairs, originally part of a set of six, can be attributed to the firm of Josef Ulrich Danhauser (1780–1829), the leading furniture manufacturer in Vienna.[9] He had many royal patrons, including Archduke Karl von Sachsen Teschen (1771–1847) and Duke Albert von Sachsen Teschen (1738–1822). The Danhauser factory produced some items in large quantities, and these pieces established the firm's reputation throughout Central Europe and Northern Italy.[10][Wolfram Koeppe 2006]Footnotes:[1] Josef Folnesics. Innenräume und Hausrat der Empire- und Biedermeierzeit in Österreich-Ungarn. 5th ed. Vienna, 1922; and Georg Himmelheber. Biedermeier, 1815–1835: Architecture, Painting, Sculpture, Decorative Arts, Fashion. Munich, 1989.[2] Joseph Gegenbach, called Canabas (1712–1797); Claude Charles Saunier (1735–1807); Georges Jacob (1739–1814); Bernard Molitor (d. 1833).[3] Nicole de Reyniès. Le mobilier domestique: Vocabulaire typologique. 2 vols. Principes d'analyse scientifique 5. Inventaire général des monuments et des richesses artistiques de la France. Paris, 1987, vol. 1, pp. 42-45, 205; and Christoph, Graf von Pfeil. Die Möbel der Residenz Ansbach. Munich, London, and New York, 1999, p. 235.[4] Hans Ottomeyer, with Ulrike Laufer. Biedermeiers Glück und Ende: Die gestörte Idylle, 1815–1848. Exh. cat., Münchner Stadtmuseum. Munich, 1987; and Achim Stiegel. Berliner Möbelkunst vom Ende des 18 bis zur Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts. Kunstwissenschaftliche Studien 107. Munich, 2003.[5] Charlotte Gere. Nineteenth-Century Decoration: The Art of the Interior. New York, 1989, pp. 188-93; Angela Völker. Biedermeierstoffe: Die Sammlungen des MAK— Österreichisches Museum für Angewandte Kunst, Wien, und des Techniscen Museums, Wien. Munich and New York, 1996, pp. 12, 69, figs. 6, 61; Pierre Arizzoli-Clémental. "Néoclassicisme." In L'art décoratif en Europe, ed. Alain Gruber, vol. 3, Du Néoclassicisme à l'Art Déco, pp. 21–127. Paris, 1994, p. 47.[6] "Recent Acquisitions: A Selection, 1996–1997." The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 55, no. 2 (Fall 1997), p. 50 (entry by Wolfram Koeppe).[7] Out of the set of six (see below), the Museum was allowed to choose the two chairs in the best state of preservation. They were examined and conserved by Mechthild Baumeister and Nancy C. Britton, Conservators, in the Museum's Sherman Fairchild Center for Objects Conservation in 1998. The accession number of the other chair is 1996.417.1.[8] John Fleming and Hugh Honour. The Penguin Dictionary of Decorative Arts. New ed. London and New York, 1989, p. 842. The technique had been in existence for some time, however; see Gabriele Fabiankowitsch and Christian Witt-Dörring. Genormte Fantasie: Zeichenunterricht für Tischler, Wien, 1800–1840. Exh. cat., Geymüllerschlössel. Vienna, 1996.[9] "Danhauser's K. K. Priv. Möbel Fabrik" translates as Danhauser's Privileged Imperial and Royal Furniture Manufactory. For similar chairs, see Vienna in the Age of Schubert: The Biedermeier Interior, 1815–1848. Exh. cat., Victoria and Albert Museum. London, 1979, p. 29, fig. 6, p. 41, fig. 15; Massimo Griffo. Il mobile dell'Ottocento: Altri paesi europei. Novara, 1984, p. 38; Georg Himmelheber. Die Kunst des deutschen Möbels: Möbel und Vertäfelungen des deutschen Sprachraums von den Anfängen bis zum Jugendstil. Vol. 3, Klassizismus, Historismus, Jugendstil. Munich, 1973, fig. 380; Angus Wilkie. Biedermeier. New York, 1987, p. 71, fig. 54, pp. 137-38, 148, fig. 138; Georg Himmelheber. Biedermeier, 1815–1835: Architecture, Painting, Sculpture, Decorative Arts, Fashion. Munich, 1989, pp. 112, 214, nos. 121, 122; Claudio Paolini, Alessandra Ponte, and Ornella Selvafolta. Il bello "ritrovato": Gusto, ambienti, mobili dell'Ottocento. Novara, 1990, p. 210; and Ian Wardropper and Lynn Springer Roberts. European Decorative Arts in the Art Institute of Chicago. Chicago, 1991, pp. 98, 137-38.[10] Georg Himmelheber. Biedermeier, 1815–1835: Architecture, Painting, Sculpture, Decorative Arts, Fashion. Munich, 1989; and Gabriele Fabiankowitsch and Christian Witt-Dörring. Genormte Fantasie: Zeichenunterricht für Tischler, Wien, 1800–1840. Exh. cat., Geymüllerschlössel. Vienna, 1996.