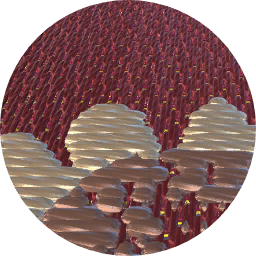

Description

This high-relief sculpture of Saint Andrew standing in a shell-topped niche was originally on an altar in Old Saint Peter’s, Rome. Tiberio Alfarano’s 1571 plan of the basilica indicates where it was located inside the front wall.[1] A drawing made before the altar was dismantled in 1606 shows, above the altar, three saints in niches separated by finely decorated pilasters: Saint Paul to the left, Saint Peter in the center, and Saint Andrew at the right. In the drawing, Andrew turns his head slightly toward Peter and embraces with his left arm the cross on which he was martyred. Paul also twists his head toward Peter, and he holds his sword of martyrdom with his right hand — his gestures are designed to mirror Andrew’s as the two flank the central saint. The reliefs of Peter and Paul — without the pilasters — are now in Boville Ernica, near Rome, where they were installed with Saint Andrew about 1612. Prominent on the structure that supported the saints in Old Saint Peter’s was the inscription "Guillermus de Perreriis Auditor hoc altare deo et SS Apostolis Dedicavit, An D MCCCCLXXXXI." [2] The French prelate Guillaume de Perrier commissioned this and several other altars for Roman churches in the 1490s. [3] Antonio Muñoz was the first to associate the Museum’s relief with the altar in Old Saint Peter’s, after it appeared on the market in 1909.[4]By the time Andrea Bregno carved the three reliefs he was nearing the end of an active and distinguished career. He is best known for funerary monuments of prelates, such as those in memory of Cardinal Ludovico d’Albret (died 1465) in Santa Maria in Aracoeli, Rome, and of Cardinal Cristoforo della Rovere and Cardinal Domenico della Rovere in Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome (died 1478 and 1501, respectively), as well as for altars, notably the Borgia Altar in Santa Maria del Popolo (commissioned 1473).[5] Many of these monuments and altars feature reliefs of single saints in niches. By the 1480s, after the influential sculptors Giovanni Dalmata and Mino da Fiesole had departed from Rome, Bregno’s large workshop dominated commissions in that city. Bregno collected antiquities, and his increasingly classicizing style reflects this interest; he was also celebrated for decorative carving on architectural ensembles, above all, the Piccolomini Altar (1485) in Siena Cathedral.[6] The solid stance of Saint Andrew’s body in the Museum’s relief and the sharply defined pleats of his robe show how closely Bregno had looked at classical sculpture in Rome. The delicate candelabrum motifs on the pilasters flanking the saint, also culled from ancient sources, give ample evidence of his refined architectural touch. Museum curator Olga Raggio related these stylistic traits to Bregno’s earlier work on the Borgia and the Piccolomini altars and affirmed that the fineness of the carving indicates that the master himself, and not his workshop, was responsible. [7] Her observation that Andrew’s features are similar to Andrea’s in the portrait of the artist on his tomb in Santa Maria sopra Minerva, Rome, may not be immediately apparent; however, there is little doubt the artist had a special affinity for his patron saint. Bregno and his workshop completed a number of similar marble reliefs for the various Perrier altars and for tombs; the Saint Andrew relief is particularly close to Saint James and Saint John in San Giovanni in Laterano, completed in Rome in 1492 – 93, just after the reliefs for Old Saint Peter’s. Often formed as triptychs of saints, reliefs by Bregno were subsequently erected in the Roman churches of San Paolo (1494), Santa Maria del Popolo (1497), and Santi XII Apostoli (undated, but evidently later in his career). Examination of Bregno’s reliefs for Santi XII Apostoli, now in the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, reveals not only that the standard set in the Old Saint Peter’s reliefs at the beginning of the 1490s was retained at the end of the decade but also how Bregno used details to vary the basic model.[8] Saint James and Saint Philip fill their niches more amply and stand taller than Andrew in his, and the architectural decoration is more detailed, including beading, moldings, and scallop shells not seen in the Museum’s example. These are additions that might occur to a sculptor while working on later formulations of his original conception. It is the sensitive workmanship of the head and hands of Saint Andrew that distinguishes it as primary. The thin face with its precisely drawn brows and the meticulously veined hands with naturalistically spaced fingers are so finely rendered as to justify Olga Raggio’s ascription of the work directly to Bregno. While the sculptor refined the motif of the standing saint, a mainstay of his production over many years, he clearly took special care with this commission for the most exalted church in Christendom.[Ian Wardropper. European Sculpture, 1400–1900, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York, 2011, no. 10, pp. 40–41.]Footnotes:[1] Tiberio Alfarano. Basilicae vaticanae antiquissima et nova structura. Edited by Michele D. Cerrati. Documenti e ricerche per la storia dell’antica basilica vaticana 1. Studi e testi (Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana) 26. Rome, 1914, p. 70.[2] Giacomo Grimaldi. Descrizione della basilica antica di S. Pietro in Vaticano: Codice Barberini Latino 2733. Edited by Reto Niggl. Codices e Vaticanis selecti 32. [Vatican City], 1972, p. 133, fig. 47.[3] Ernst Steinmann. "Andrea Bregnos Thätigketi in Rom." Jahrbuch der Königlich Preussischen Kunstsammlungen 20 (1899), pp. 216–32, pp. 226 – 27.[4] Antonio Muñoz. "Ancora delle opera d’arte di Boville Ernica provenienti da S. Pietro in Vaticano." Bolletino d’arte 6, no. 6 (1912), pp. 239–45, p. 239. [5] See Emilio Lavagnino. "Andrea Bregno e la sua bottega." L’arte 27 (1924), pp. 247–63 and Gianni Carlo Sciolla. "Profilo di Andrea Bregno." Arte lombarda 15, no. 1 (1970), pp. 52–58 for overviews of these works.[6] Claudio Crescentini. "Roma, Sisto IV Della Rovere e il ‘gran compositore’ Andrea Bregno: Antiche Cristiane Memorie Marmoree." In I Della Rovere nell’Italia delle corti, vol. 2, Luoghi e opera d’arte, edited by Bonita Cleri, Sabine Eiche, John E. Law, and Feliciano Paoli, pp. 7–25. Proceedings of a conference held at Palazzo Ducale, Urbania, September 16–19, 1999. Urbino, 2002. For Bregno’s interest in classical art, see Michael Greenhalgh. "Andrea Bregno and the Antique." In Andrea Bregno: Il senso della forma nella cultura artistica del Rinascimento, edited by Claudio Crescentini and Claudio Strinati, pp. 244–63. Florence, 2008. Specifically on Bregno’s work in the Piccolomini Chapel in Siena Cathedral are: Francesco Caglioti. "La Cappella Piccolomini nel Duomo di Siena, da Andrea Bregno a Michelangenlo." In Pio II e le arti: La riscoperta dell’antico da Federighi a Michelangelo, edited by Alessandro Angelini, pp. 386–481. Siena and Cinisello Balsamo, 2005 and Francesco Caglioti. "Andrea Bregno, Pietro Torrigiani e Michelangelo, Cappella Piccolomini, e Giovanni di Cecco, Madonna col Bambino." In Le sculture del Duomo di Siena, edited by Mario Lorenzoni, pp. 174–81. Cinisello Balsamo, 2009.[7] Olga Raggio in The Vatican Collections: The Papacy and Art. Exh. cat. The Metropolitan Museum of Art; Art Institute of Chicago; Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco; 1983–84. New York, 1982, p. 43. [8] Ulrich Middeldorf. Sculptures from the Samuel H. Kress Collection. Vol. 1, European Schools, XIV–XIX Century. Complete Catalogue of the Samuel H. Kress Collection. London, 1976, p. 65; Michael Kühlenthal. "The Monument of Raffaele della Rovere in Santi Apostoli in Rome." In Andrea Bregno: Il senso della forma nella cultura artistica del Rinascimento, edited by Claudio Crescentini and Claudio Strinati, pp. 208–25. Florence, 2008, p. 215 and fig. 4, maintains these late reliefs are from Bregno’s workshop.