Description

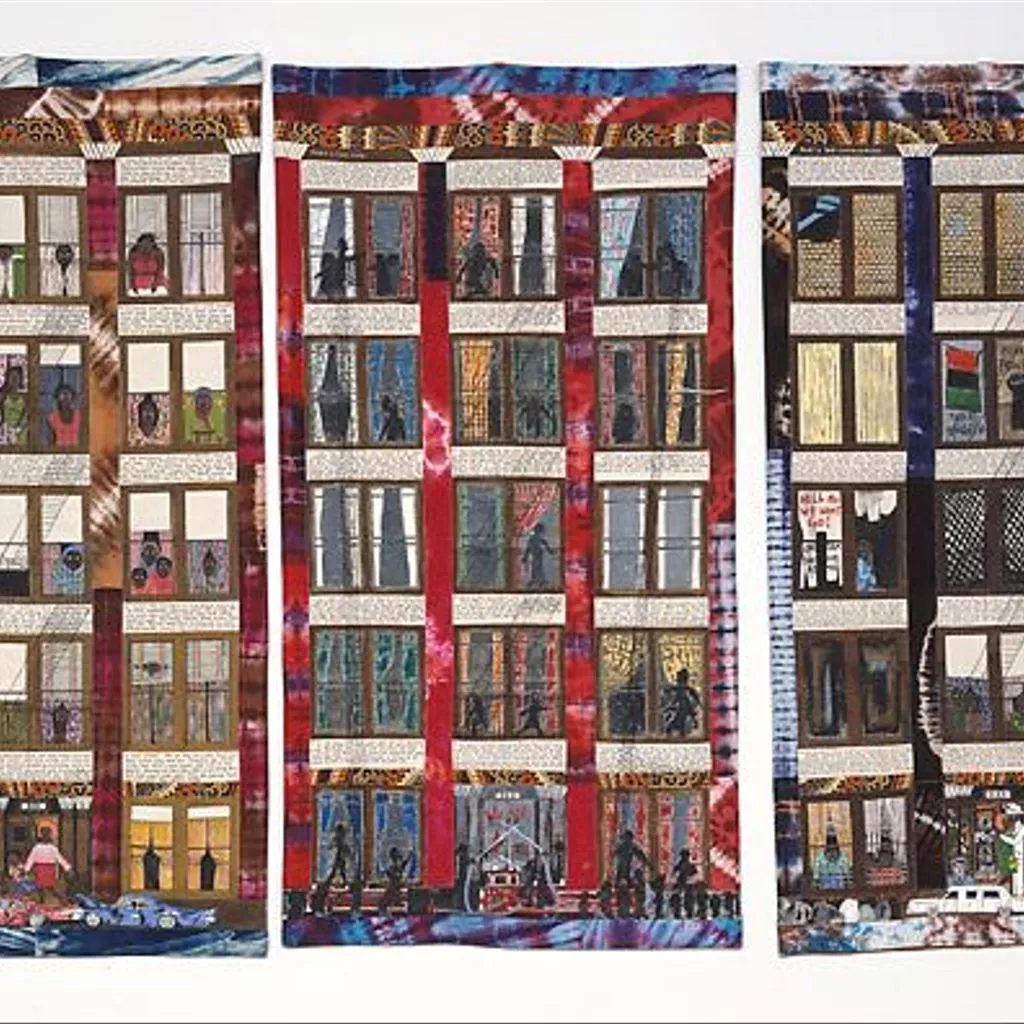

In this triptych, Ringgold combines language and imagery to structure her complex, fantastical narrative of survival and redemption set in an apartment building in Harlem. By 1983, Ringgold had immersed herself in a new art form, story quilts, which seemed a natural progression from her painting, fabric sculpture, and performance art. With story quilts, this activist artist—concerned throughout her career with issues of feminism and race—creates a new expression that acknowledges cultural and personal history. Domestic arts—sewing, quilting, weaving—have long been associated with women, and quilting reflects the folk traditions (and the struggles and achievements) of Black women. For Ringgold, the fact that her mother was a dressmaker and fashion designer adds another evocative layer of meaning and history to an already loaded medium. Storytelling, too—the expression of narrative—carries dense referents with legends, tales, even jokes associated with African-American community life and oral history.In Street Story Quilt, one stylized Harlem facade—a grid of fifteen windows—is depicted three times at different moments in a story that transpires over decades. Handwritten text fills panels above each window. In the first panel, "The Accident," a character named Grace narrates the story of ten-year-old A.J. and his grandmother, Ma Teedy, who have just witnessed a car accident that kills A.J.'s mother and four brothers. The central panel, "The Fire," depicts the devastating effects of a blaze inadvertently set by A.J.'s drunken father, who dies in the fire. Text reveals that "A.J. ran away from home right after big Al's funeral. He was picked up a few days later for sellin dope to a cop." The traumas continue, one compounding the other, but through it all, Grace notes: "Say what you want 'bout Ma Teedy but she was a real woman … I like her because she a survivor. Always keep herself and her family lookin good."The final panel is "The Homecoming," in which A.J., now a man who has fully redeemed himself and become a successful writer and actor, returns to the scene to pick up his grandmother and take her back to California with him. Grace describes her insights: "I knew that boy was special from the day he was born. He was just different, with his badness. Peoples used to talk bout him after his Ma died, then his Pa died and he had to run and hide from the Mafia. That's that kick in the ass the black man gets. But A.J. done made that kick into a kiss. And I just love him cause he ain forget Ma Teedy. An he ain forget where he come from, or who he is."