Description

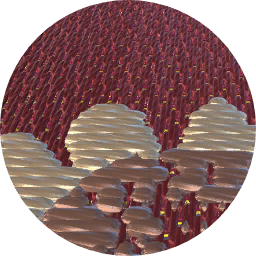

Layette pincushion, baby's, satin and pinwork with the words 'Welcome dear babe', made in England, 1788.

Baby's layette pincushion, of cream-coloured satin with a matching tassel of silk thread at each corner. The front of the pincushion is stuck with hand made pins to show an inscription and a star-like flower within a circle of linked rings resembling stylized flowers; the initials M P are above and the date 1788 below. The pincushion is further decorated in pins with a straight line around each edge; the back of the pincushion is plain.

Roger Warner (1913-2008) was a well respected antiques collector as well as dealer.

Layette pincushions are just one type of these objects: pincushions in general have been available since at least the 17th century, and were once of much greater importance sartorially than they are now because pins were used to fasten garments, as well as for needlework and lace-making. Layette pincushions like this one were once customary presents to a new mother, and were most popular between about 1770 and 1890. It was best to give them after the baby arrived, as there was a superstitious belief that they could increase the pain felt by the mother during birth: 'For every pin a pain' and 'More pins, more pain' were two of the traditional sayings. And at a time when many problems could arise during childbirth, some felt that it was taking too much for granted to give birth presents before the baby had arrived.

Layette pincushions were in some ways the equivalent of the birth congratulation cards we now send, as the pins were often arranged to show good wishes, sometimes in verse. Shorter messages such as 'Welcome Sweet Babe' or 'Welcome Little Stranger' (a coy way of referring to an unborn or newborn baby) were more typical. It took considerable skill to form the words and motifs in pins, and mistakes could damage the fabric. On some later examples it is possible to see a way of doing this more easily. The words and decoration were drawn in pencil on the surface of the fabric first, something which would be invisible after the pins were stuck in. And this method was almost foolproof after 1878, because closed pins became available, and the pincushions were almost purely decorative and commemorative.