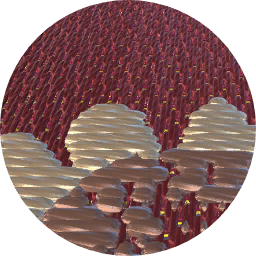

Description

The soft-paste porcelain factory at Capodimonte was established in 1743, but experiments to produce porcelain in Naples may have begun three to six years earlier.[1] Due to the king of Naples, Charles III’s (1716–1788) interest in porcelain, initial attempts were made to produce the ceramic ware, but at the same time it remains unclear the degree to which his wife, Maria Amalia of Saxony (1724–1760), encouraged his involvement. The granddaughter of August II (1670–1733), commonly known as Augustus the Strong, elector of Saxony, king of Poland, and founder of the Meissen factory, Maria Amalia brought Meissen porcelain to Naples as part of her dowry in 1738, [2] but perhaps equally important, Charles III would have been well aware of the prestige conferred on her family as a result of Meissen’s success. The fact that he also founded royal workshops for tapestries and for pietre dure (hardstones) indicates Charles III’s recognition of both the political and economic advantages of an active royal patronage. By the early 1740s, a number of skilled artists and technicians had been engaged to further the king’s pursuit of porcelain, and sufficient progress was made by 1743 to warrant renovating a building on the grounds of the Royal Palace of Capodimonte, just outside of Naples, for the new porcelain factory. While the initial attempts to assemble a skilled workforce had presented obstacles,[3] those ultimately hired for the most important positions established Capodimonte as one of the most artistically successful factories in Europe. With Gaetano Schepers (Italian, d. after 1764) in charge of the porcelain paste, Giovanni Caselli (Italian, 1698–1752) directing the painting workshop, and Giuseppe Gricci (Italian, ca. 1700–1770) in charge of the modelers, the factory produced works of remarkable distinction and variety.The figures of The Mourning Virgin and Saint John the Evangelist are among the earliest sculptures made at Capodimonte and almost certainly date to 1744, a year after the factory moved into its official quarters. The base of the Virgin bears an incised g.gricc, and it is one of only two works known to have Gricci’s signature.[4] The Mourning Virgin and Saint John are ascribed the date based on a documentary reference to a figure of the Pieta modeled by Gricci in March 1744 and to a Madonna that he modeled several months later, either of which might refer to the Museum’s Mourning Virgin.[5] The two figures now at the Museum belong to a very small group of works made by Gricci in the years around 1744, and they are remarkable for their scale, their reductive but expressive modeling, and their emotive power.[6] As has been noted by Angela Carola-Perrotti, the soft-paste body produced at Capodimonte was not conducive to modeling in fine detail,[7] and Gricci seems to have recognized this constraint and responded with a sculptural style in which simplified forms and gestures could be used to convey emotion and meaning to great effect.The Mourning Virgin is depicted seated with her hands, clasped, her neck extended back, and her head turned as she looks upward. Her anguish is conveyed by an open mouth and visible tears below her left eye. It is probable that The Mourning Virgin was originally part of a Crucifixion group, and her upward glance would have been directed at the figure of Christ on the Cross, now missing. The standing figure of Saint John is composed with his head in profile, looking down and supporting his chin with his hand in a pose traditionally associated with contemplation. Both figures are supported on bases suggestive of rockwork with irregular profiles. One side of each base is indented, suggesting they were intended to be joined with another base to support a figure now missing. While it is very likely that both figures now in New York were produced to be part of the same Crucifixion group, it is also possible that they were intended for ensembles of different compositions. It is difficult to imagine The Mourning Virgin in a composition other than a Crucifixion group given her pose, but conceivable the Saint John was originally part of a Lamentation or Pieta group, which would make his downward glance more understandable. Both figures reflect the early technical challenges encountered by the factory. The glaze on The Mourning Virgin is pitted in some areas and has bubbled in others, while the glaze of the Saint John has a slight but noticeable yellowish hue. There are small firing cracks in each figure, and the Saint John lists slightly to one side. However, these minor flaws do not diminish the artistic and emotional impact of the two figures. Gricci has created two porcelain sculptures that rival in their expressiveness the finest of Johann Joachim Kandler’s (German, 1706–1775) works at Meissen as well as the sculptures that would be produced at the Ginori factory in the town of Doccia within a few years (1997.377). It is all the more remarkable that Gricci could create these works with Capodimonte’s soft-paste body, which precluded the sculptural definition allowed by hard paste. Gricci has maximized the notably glassy glaze of the two figures to create a play of light that enlivens the surfaces, and the warm, creamy quality of the ceramic body, deliberately left undecorated, underscores the particular appeal of soft-paste porcelain.Footnotes 1 For more information on the factory, see Stazzi 1972; Carola-Perrotti 1986b; Carola-Perrotti 2010; Agliano 2013; Agliano 2014, pp. 272–74.2 Carola-Perrotti 2013, p. 207.3 Ibid.4 In the literature on Capodimonte porcelain, The Mourning Virgin is commonly published as the only work signed by Gricci, but there is a figure of Saint John of the same model as that in the Museum that also bears Gricci’s signature, which appears as g.gricc. This figure was in a private collection in Italy when it was brought to the attention of the Museum in 1999. Information and photographs in the curatorial files, Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.5 Stazzi 1972, p. 318. According to Stazzi, the reference to the Pieta is not to a group but rather to a single figure, which he suggests might be the Museum’s Mourning Virgin.6 The group includes a Pieta group in the Museo Duca di Martina, Naples (Silvana Musella Guida in Porcellane di Capodimonte 1993, pp. 154–56, no. 86); a figure of Saint John of the same model as that in the Museum in a private collection, Italy; a figure of Saint John of a different model in the Museo Correale, Sorrento (Buccino Grimaldi and Cariello 1978, p. 113, no. 4, pl. lxxii); a Virgin of the Immaculate Conception, Museo di Capodimonte, Naples(Patrizia Piscitello in Sovrane fragilità 2007, p. 39, no. 14a, ill. p. 38); and a Corpus on the New York art market in 2011 (Carola-Perrotti 1986a, p. 27, ill. nos. a–c).7 Carola-Perrotti 2010, p. 90.