Description

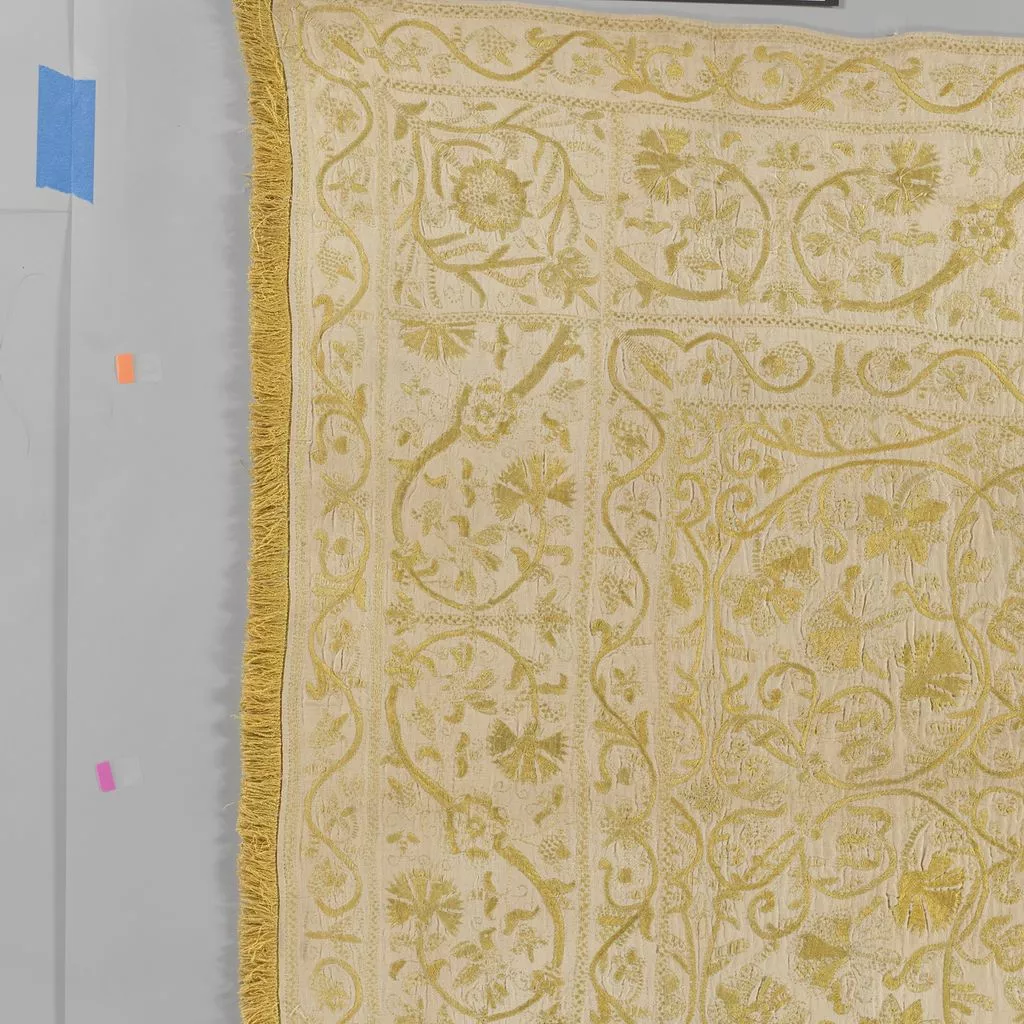

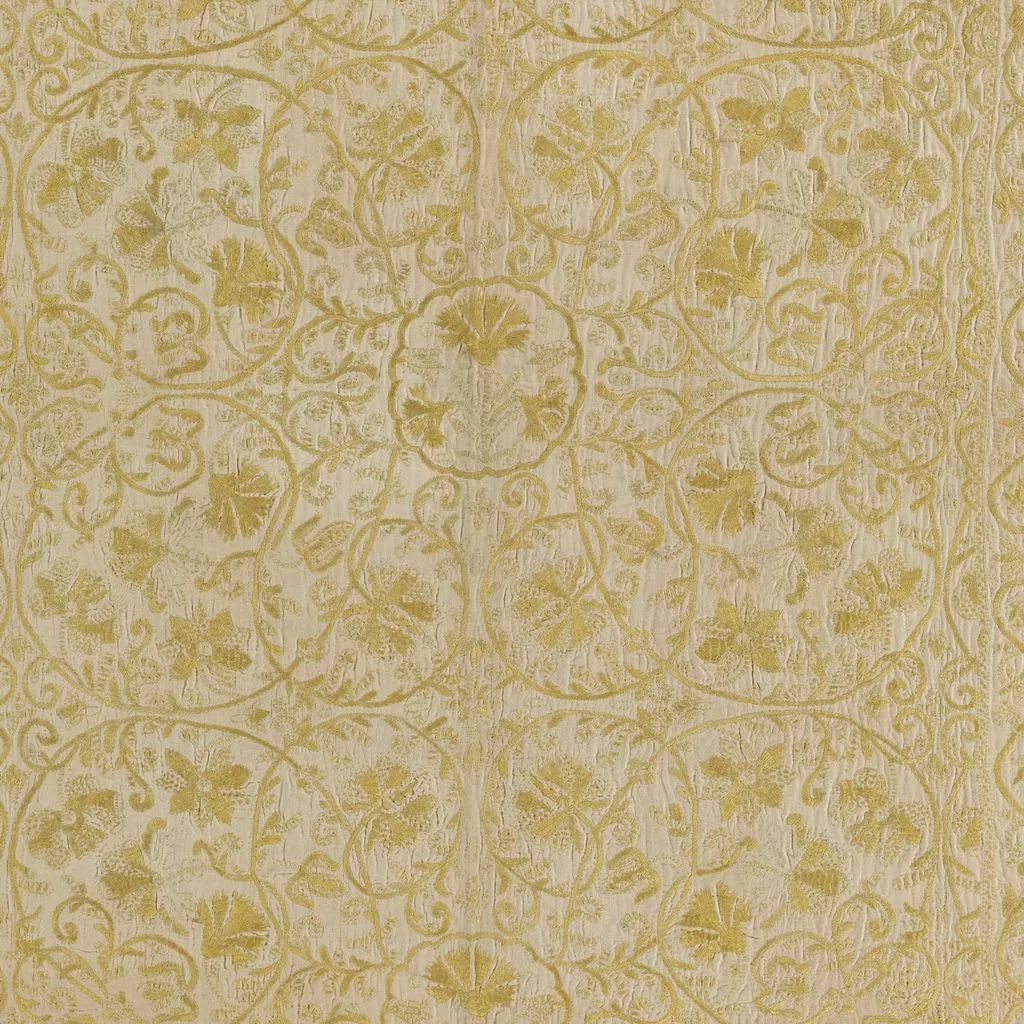

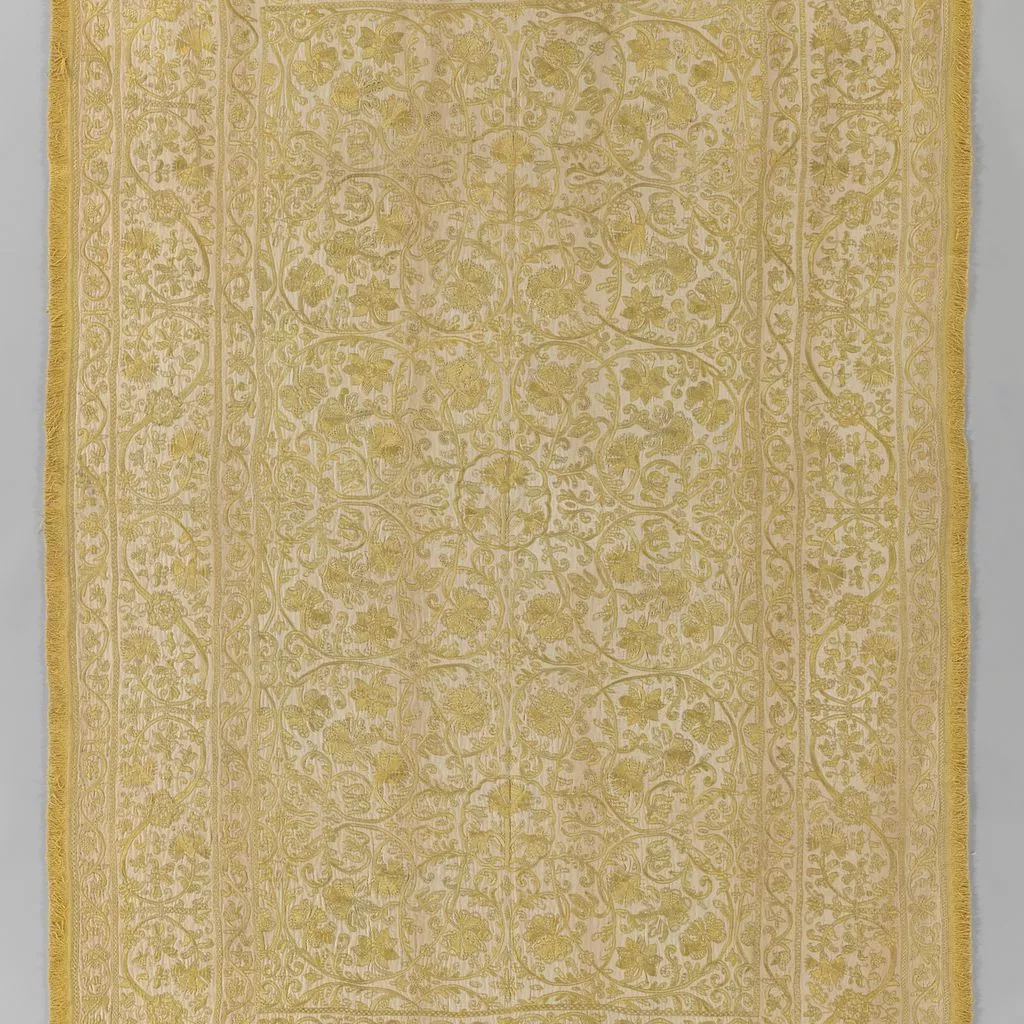

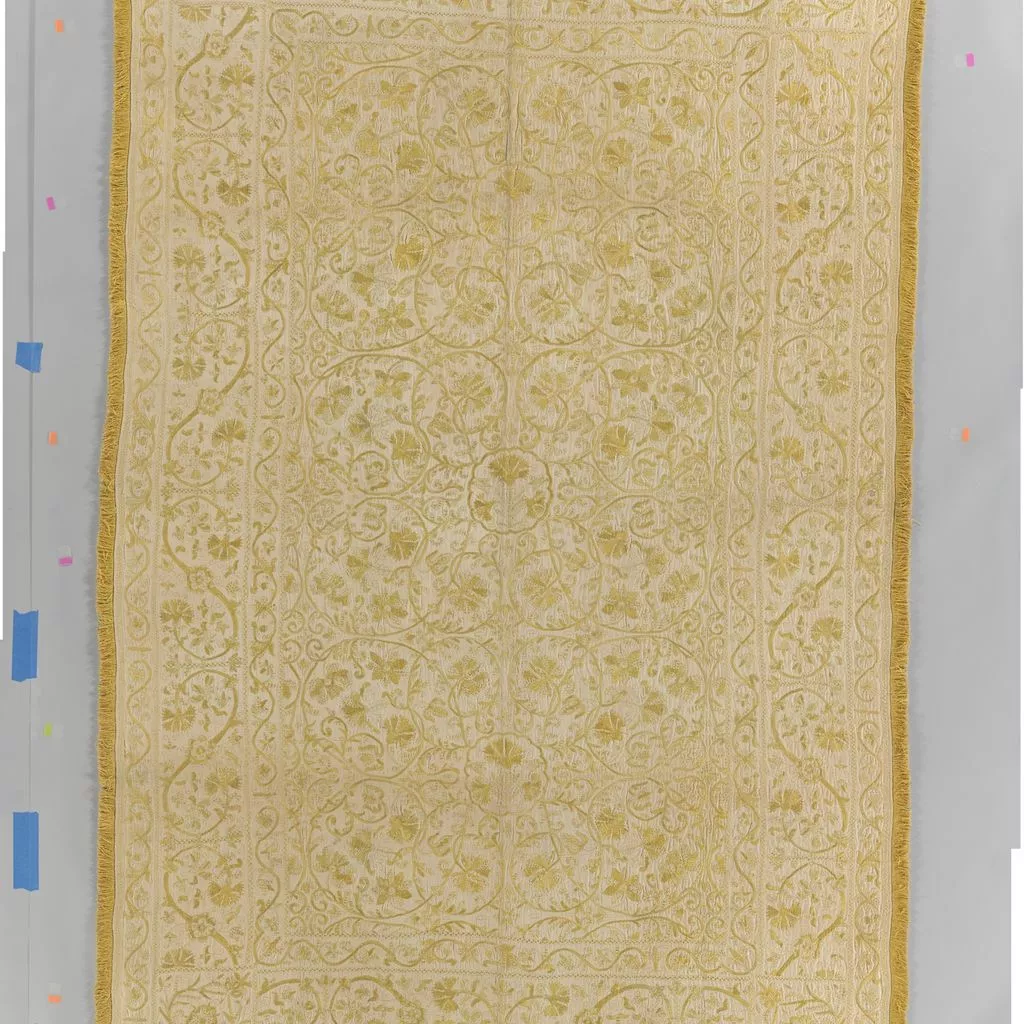

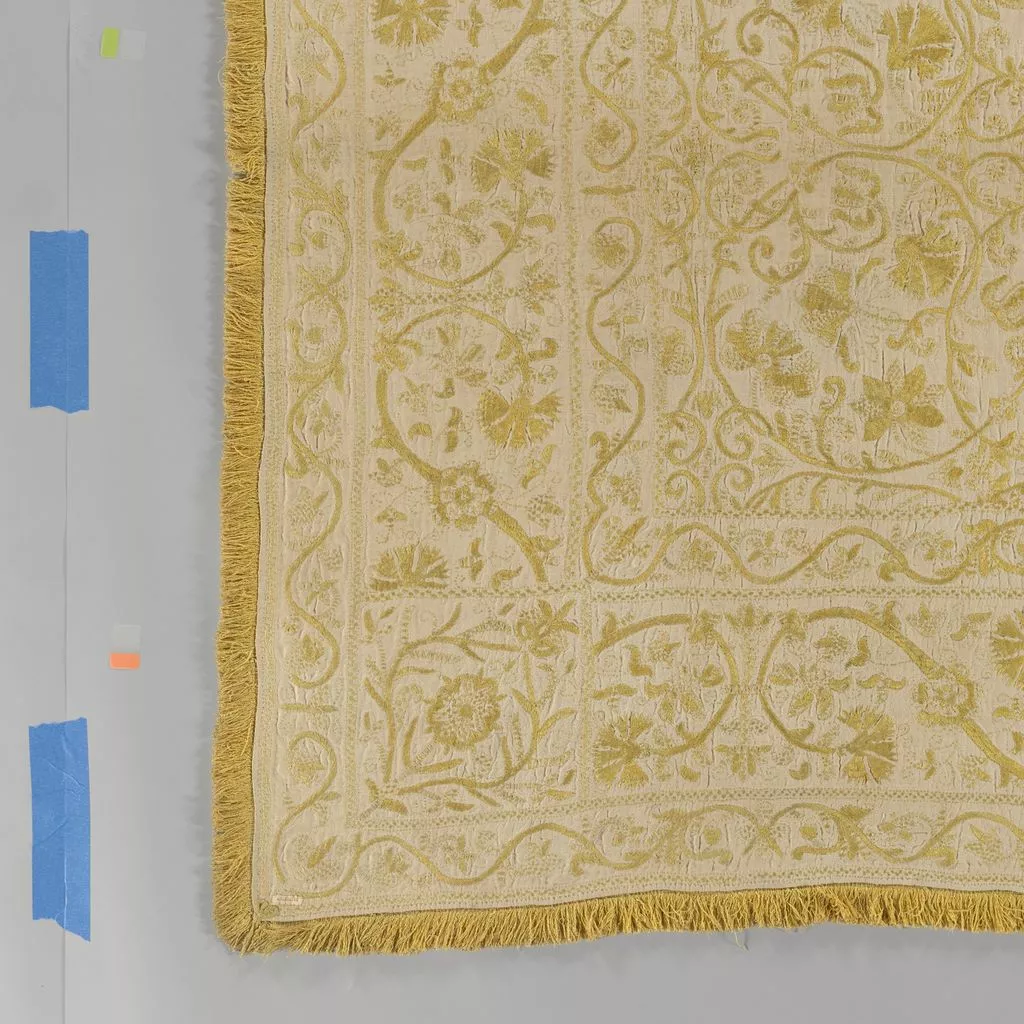

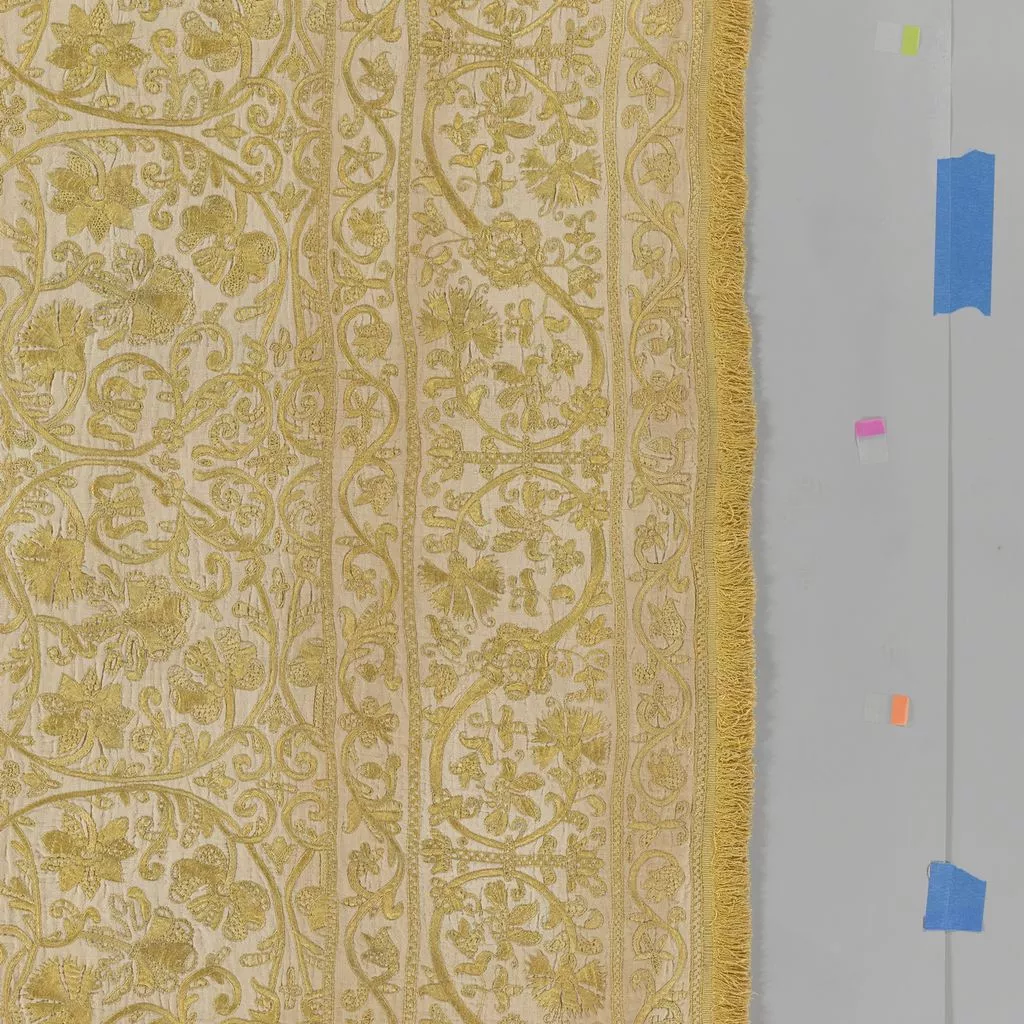

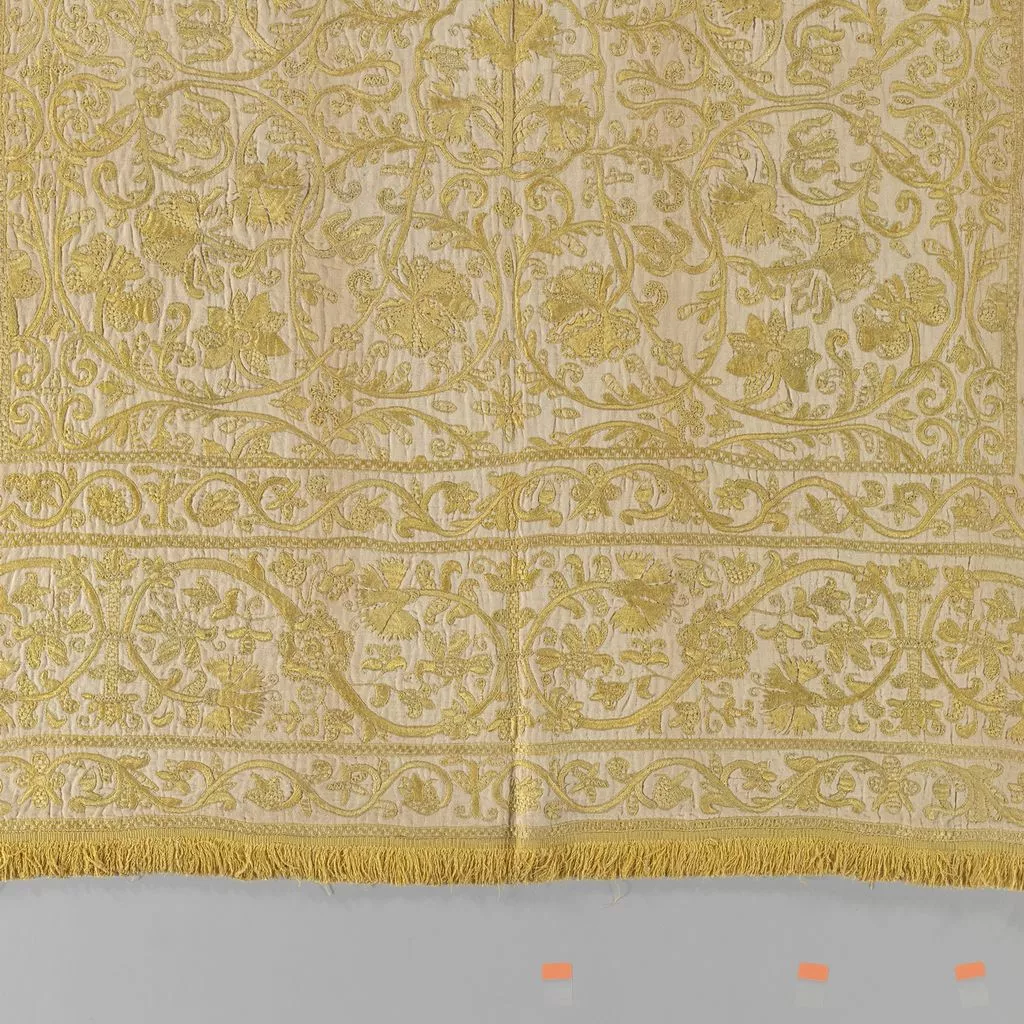

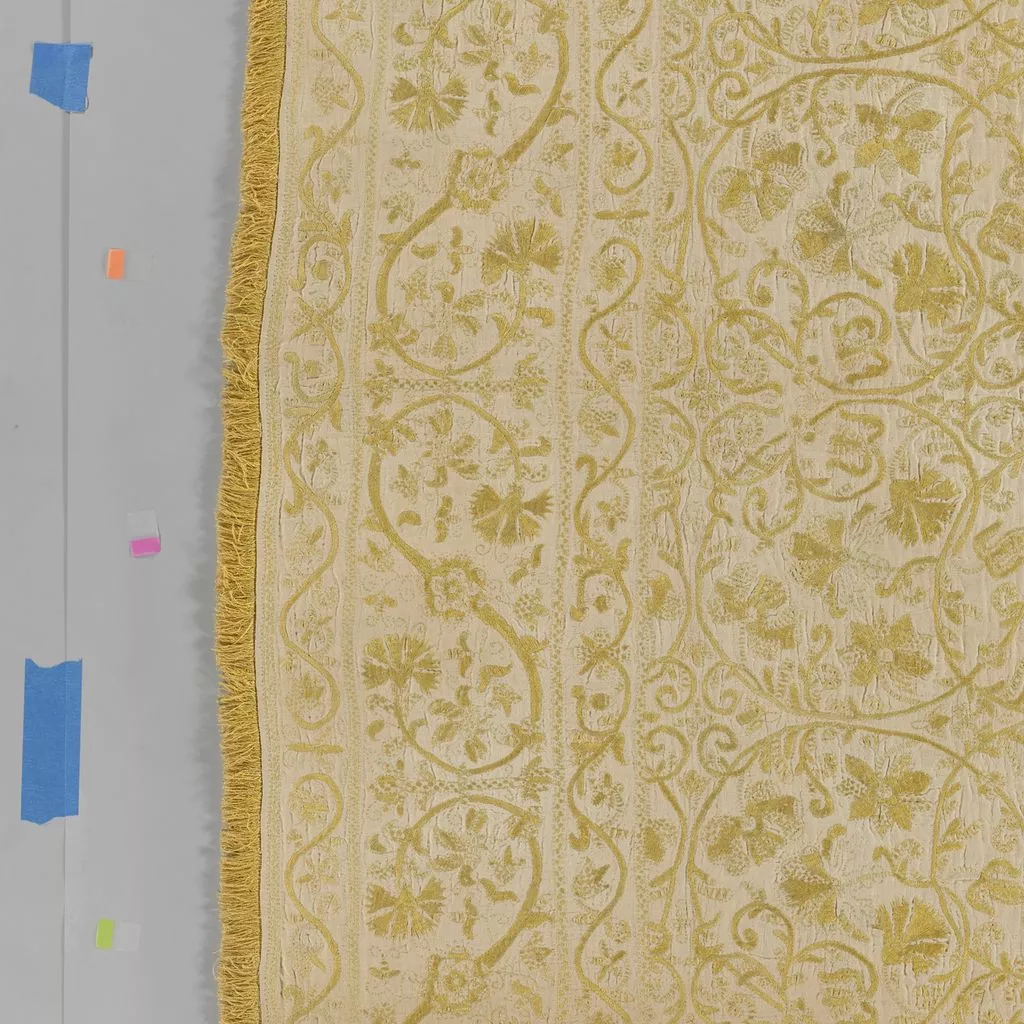

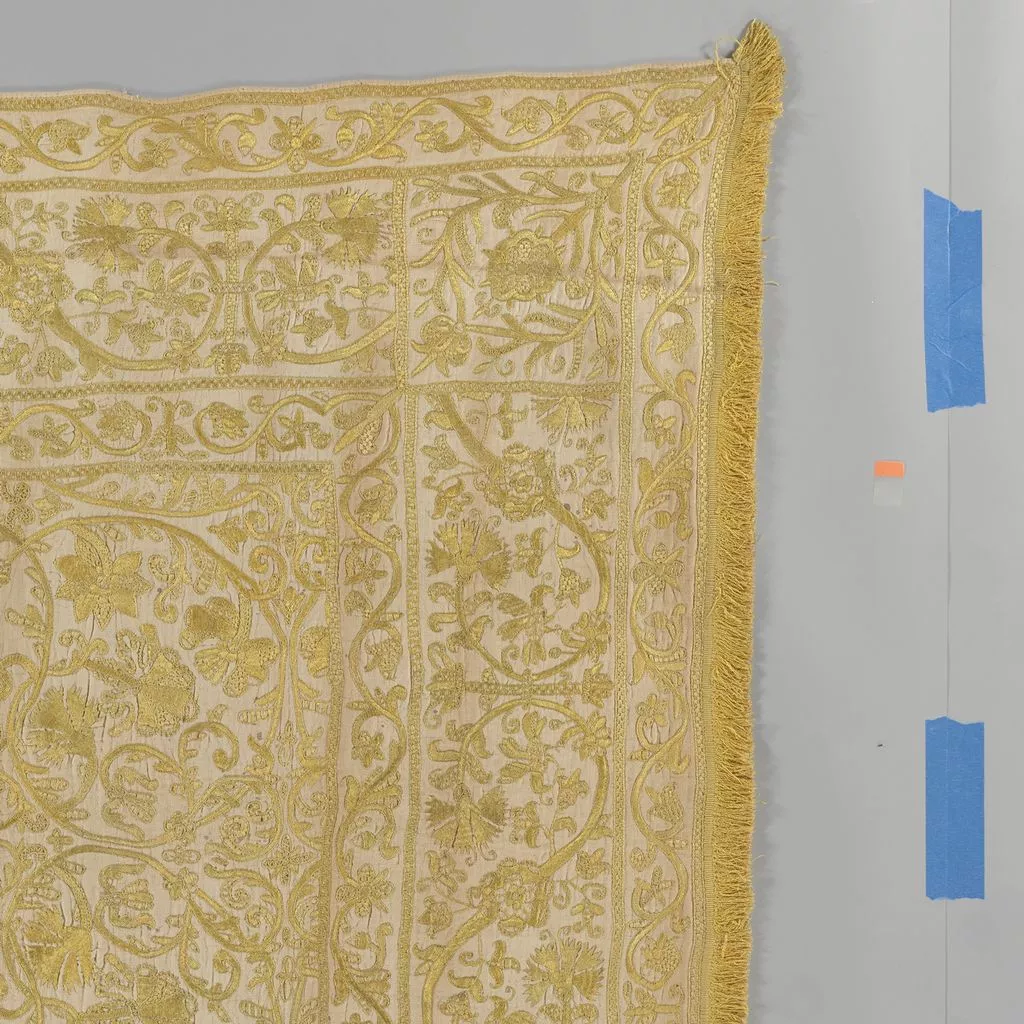

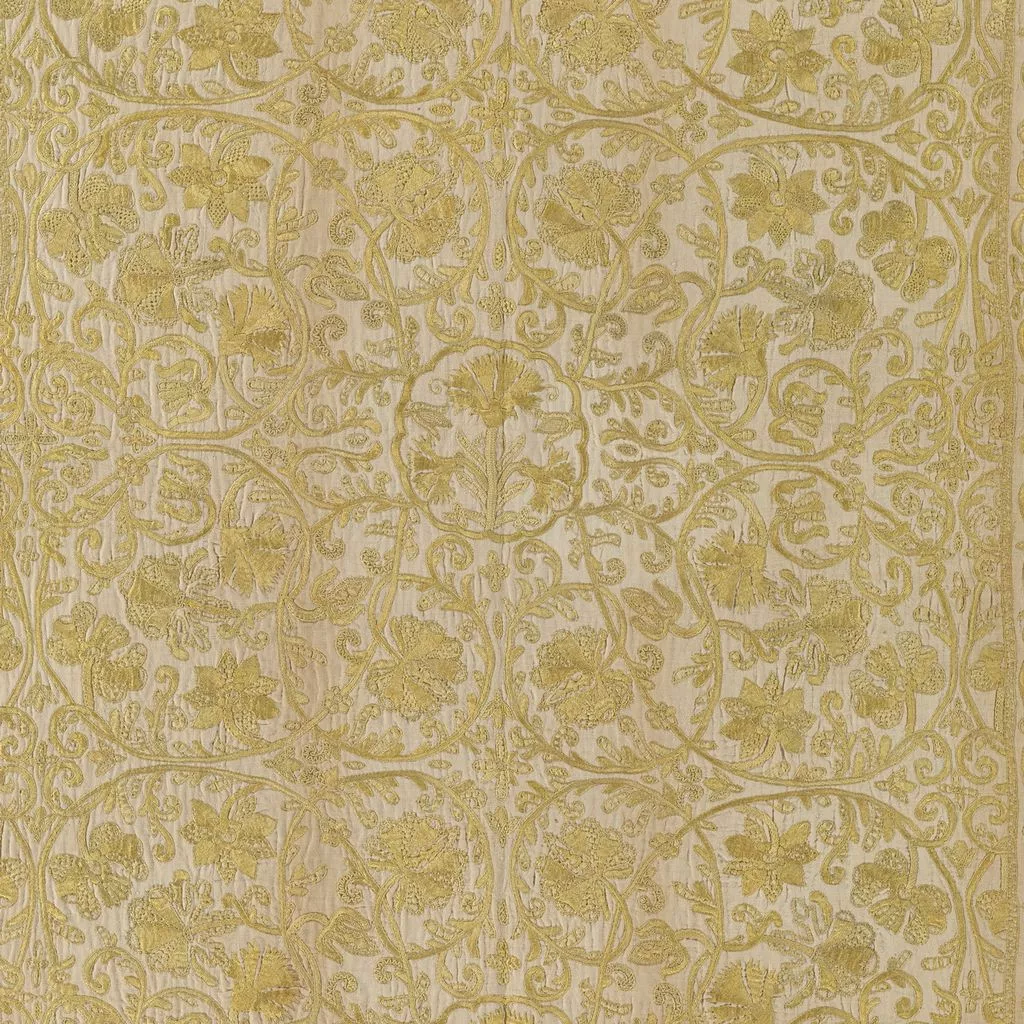

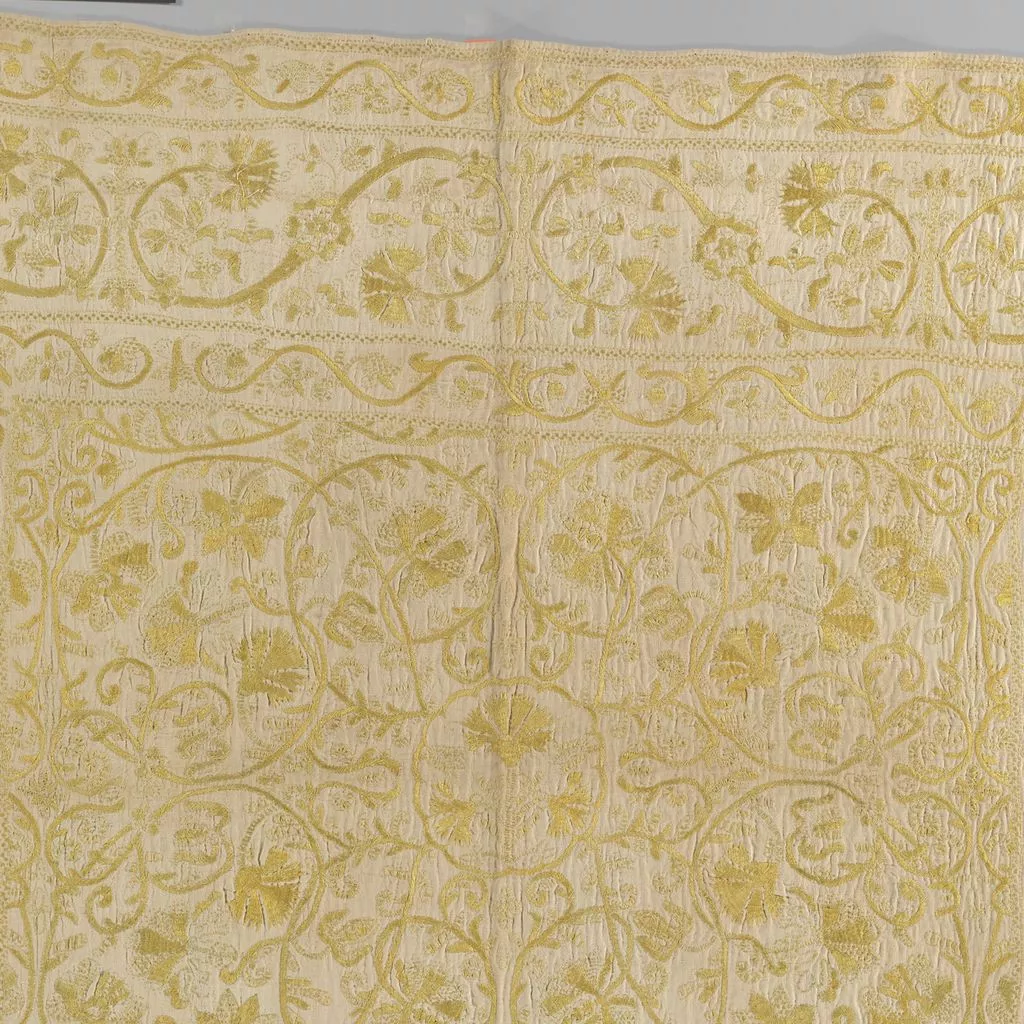

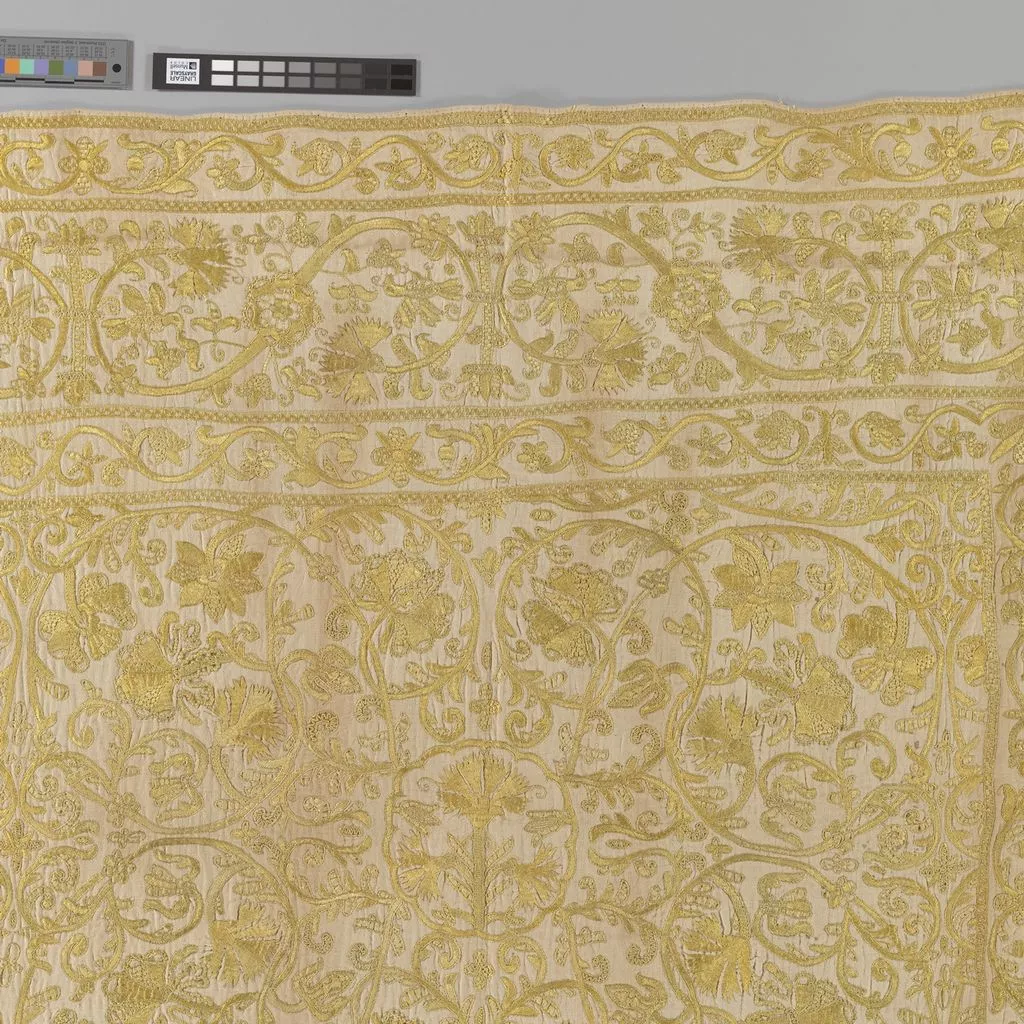

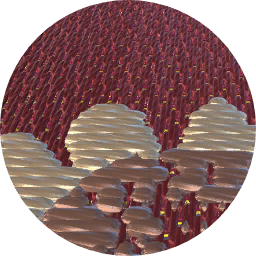

Silk-embroidered linen covers were common furnishings in Iberian households. The proportions of this example indicate that it was used over a table rather than on a bed. The floral designs—elegant Renaissance-style scrolling vines with carnations, irises, and other flowers as well as hummingbirds seeking nectar—are constructed with brilliant yellow silk embroidered on a natural linen ground (outlines in brown tannin ink, drawn for the embroiderers to follow, are still visible in some areas). The golden yellow color, a favorite in Iberia for textiles, was derived from weld, a local dyeplant that thrived in the region and was relied on for its brilliance and durability.¹ Although the contrast between the yellow silk and the ecru ground echoes that of certain Indian embroideries made in Bengal and imported into Portugal and Spain in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries (see MMA1975.4, MMA 23.203.1), the ease of the design and the variety in stitch type (including satin, chain, and stem as well as various kinds of knots and filling stitches) help identify this as a European cover. The configuration of the cover’s decorative elements constitutes a basic format that may have originated in Islamic Spain. In particular, the large central field with a series of outer borders, including a broad center border flanked, or "protected," by narrower guard borders on either side, was an established style for carpets throughout the Islamic world and one that influenced other regional textile designs, notably Spanish embroidery (the demarcation of the four outer corners in this example may, however, be more Iberian than Islamic in character). This design approach, in turn, was transmitted around the world via Spanish and Portuguese colonial administration and trade, from tapestries made by Andean weavers in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Peru (see MMA 56.163) to Asian and Indian embroideries intended for the European market (see MMA 1975.208d). Given the shared heritage of Portugal and Spain, especially during the sixteenth century, when both countries were united under a single ruler, it can be difficult to differentiate the embroidery production of one from the other.² Both regions had longstanding traditions of fine textiles, from folk works to commissions made by professional guilds for the Church and royal court. This example lies somewhere in between: although the cover was intended for actual household use, its intricate style and high quality suggest that it was made for a person of means and status. [Melinda Watt, adapted from Interwoven Globe, The Worldwide Textile Trade, 1500-1800/ edited by Amelia Peck; New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art; New Haven: distributed by Yale University Press, 2013] 1. Nobuko Shibayama in the Department of Scientific Research, Metropolitan Museum, analyzed the yellow dye using High Performance Liquid Chromatography- Photo Diode Array (HPLC-PDA) and identified the source as weld. 2. For Spanish and Portuguese textile traditions, see May, Silk Textiles of Spain, Eighth to Fifteenth Century; Weibel, Two Thousand Years of Textiles; Real, Spanische und portugiesische gewebe; and Vaz Pinto, Bordado de Castelo Branco: Catálogo de desenhos, vol. 1, Colchas.