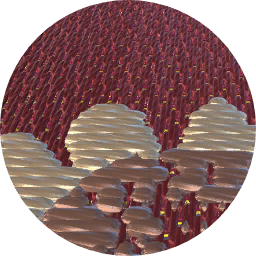

Description

These roundels (see also 27.112) from the Conde de Las Almenas collection in Madrid were separated after auction in New York in 1927 but reunited in the Museum a few years later. They may have been part of a larger series, since there is no reason — biblical or historical — to show Saint Agnes and Saint Jerome together (the pairing may reflect the patrons’ given names, however). Both Agnes and Jerome were popular subjects in the religious art of Spain. Jerome is shown, pen in hand, writing a book, presumably his Latin translation of the Bible, known as the Vulgate. His robe has the ermine-fringed collar of a cardinal and his hat hangs on the wall behind him; the head and a paw of the lion he befriended after extracting a thorn peek out beneath his arm. The virgin martyr Agnes holds her attribute, a lamb. Jerome is often depicted alone, but since he was one of the Four Fathers, or Doctors, of the Church, he may originally have been joined by three male saints and four female saints, to make a series of eight. Whether as a pair or as many as eight, the roundels could have been decorations for one of the large retables, or altar shelves, that filled churches during this period, but their sumptuous nature would also have suited a palace. The richly carved and painted garlands of fruit and flowers, a type of ornament popularized in glazed terracotta work by the Della Robbias in Italy and widely imitated in Europe, would have brought the saints into harmony with a secular interior.As a medium for sculpture, alabaster was often used in northeastern Spain, where it was quarried.[1] Even such a costly material as alabaster was frequently painted in the Renaissance. While the natural beauty of the stone is left unadorned in the carefully chiseled striations of Jerome’s sleeves, the fur of his cloak, or the billows of Agnes’s dress, most of the reliefs’ surfaces have been defined by color. Dark green leaves contrast with white and red fruit and flowers in the garlands; carnation hues blush on Agnes’s cheeks and gold highlights her tresses, while tones of black emphasize Jerome’s gnarled beard; and gilding picks out the hems and ermine tails of their robes. Without pigment, the windmill and low-relief landscape behind Agnes would lack visual clarity. Spanish wood sculpture was routinely painted, and the roles of entallador (carver) or escultor (sculptor) were clearly separated from that of the encarnador (painter of flesh tones) or estofador (painter of draperies). While wooden sculpture was completely covered with paint and required the hand of several specialists, alabaster was more selectively painted, and possibly a single artist — quite likely not the carver — was responsible for the coloring here. Diego de Siloé’s Virgin and Child (ca. 1519 – 28, Victoria and Albert Museum, London) is another example of the partial painting of alabaster: only hair, drapery, and facial features received coats of pigment. The carving of these roundels is most attractive, and the coloration complements rather than detracts from the sculptor’s skill. Jerome’s bony fingers and gaunt cheekbones deliberately contrast with the voluptuous smoothness of Agnes’s flesh. The textures of their hair and the swelling forms of the fruit were brilliantly rendered by chisel first, and only then enhanced by the painter’s finesse. Both sculptor and painter must have delighted in the trompe l’oeil fly that has just landed on Jerome’s book. Jerome’s torso, bursting from the garland’s confines, reflects trends of Mannerist art in Spain in the middle of the sixteenth century. Stylistic traits and material clues (such as the use of alabaster) suggest that the roundels were made in the region of Aragon. James Rorimer thought that Damián Forment, a famous Spanish sixteenth-century artist active in Poblet, Huesca, and Saragossa might have executed them.[2] Other scholars have offered attributions to sculptors less well known than Forment. John Goldsmith Phillips found similarities between them and sculptural work on the sacristy doors of Cuenca Cathedral, which Manuel Gómez-Moreno thought were possibly by Diego de Tiedra.[3] Although none of these attributions has been agreed upon, recent scholars have continued to locate the roundels’ place of origin in Aragon rather than Castile.[4][Ian Wardropper. European Sculpture, 1400–1900, In the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York, 2011, no. 22, pp. 74–76.]Footnotes:[1] Marjorie Trusted. Spanish Sculpture: Catalogue of the Post-medieval Spanish Sculpture in Wood, Terracotta, Alabaster, Marble, Stone, Lead and Jet in the Victoria and Albert Museum. London, 1996, p. 11.[2] James R. Rorimer. "A Sixteenth-Century Alabaster by Damian Forment." Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 23, no. 12 (December 1928), pp. 309–11. [3] John Goldsmith Phillips. "A Sixteenth-Century Spanish Sculpture." Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 29, no. 4 (April 1934), pp. 68-69, p. 68; Manuel Gómez-Moreno. Renaissance Sculpture in Spain. Translated by Bernard Bevan. Florence, 1931. [Reprint ed., New York, 1971. Originally published as La escultura del Renacimiento en España. Florence, 1931.], pp. 56 – 57, pl. 49.[4] Marjorie Trusted, oral communication and letter of 2010 in the curatorial files of the Department of Sculpture and Decorative Arts, Metropolitan Museum. Manuel Arias, deputy director of the Museo Nacional de Escultura, Colegio de San Gregorio, Valladolid, kindly confirmed that in his opinion the reliefs date from 1500 to 1550 and are likely to have been made in Aragon (communication of summer 2010).