Description

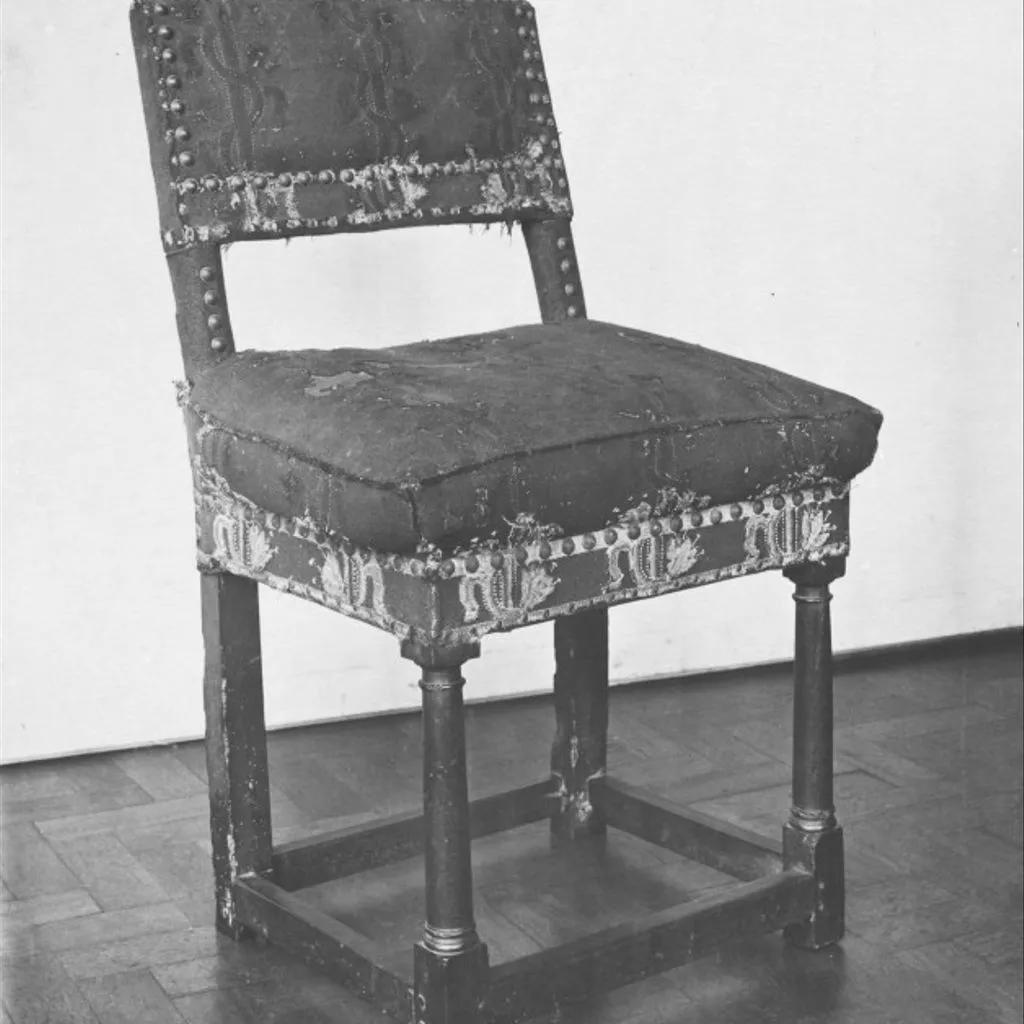

Early 17th-century English chair, walnut and stained beech, with original upholstery on back and seat, in blue wool with appliqué embroidery and trimmings (embroidery and trimmings largely missing but well preserved on back of seat)

In the 17th century this type of chair was known as a backstool, revealing its origins, and its perception at the time, as a stool with an added back, rather than as a chair without arms. Part of the explanation for this is that backstools were made in sets, like stools, whereas an armchair was traditionally a singleton, and in many houses there would have been just one, to be occupied by the most important person present (the owner or an honoured guest). The term 'backstool' remained in use for much of the 18th century - long after 'chair' also gained currency, and long after armchairs began to be made in sets (in the late 17th century).

The furniture historian Percy Macquoid claimed that this kind of chair 'was termed a farthingale chair', in the belief that the type was devised to accommodate the farthingale dress worn by women in the late 16th and early 17th centuries (The History of English Furniture, Vol. I, The Age of Oak (1904), p. 179). This romanticising term was retained by historians of furniture for much of the 20th century. See under References.

The chair has been re-polished with a dark-pigmented wax, probably in a misguided attempt to make it look like oak. This intervention very likely took place in the early 20th century, perhaps when F. C. Harper acquired the chair, or possibly earlier.

The beech back legs may well have been stained originally, to look like the walnut used for the rest of the frame. The back legs are continuous with the upright members of the upholstered back-frame, so they are made of beech to avoid wasting walnut - a much more expensive wood - in areas where it would not be seen. The convention of using beech, stained where visible, for the full-height back uprights of an upholstered chair continued well into the 18th century (as long as walnut remained the principal wood used for fashionable furniture).

Chair

About 1600–20

England

Walnut and beech

Upholstery (original): feather-filled canvas cushion; wool cloth decorated with applied silk embroidery on canvas; silk braid and fringe

Nails: brass

Museum no. W.1-1912

The first stage in the development of fixed upholstery was to tack a cushion to the seat frame. It was supported by a stout base cloth and often by webbing, as here. The blue show cover was stretched over the cushion and fixed with widely spaced brass nails set over braid. Silk embroidery, braid and fringe would have added to the effect.

[01/12/2012]

This is a remarkable survival of an early 17th-century 'backstool' with its original upholstery, nearly 400 years old. The 'backstool' was essentially a chair without arms, but as the name makes clear, it evolved by adding a back to a stool rather than by taking the arms away from a chair. Before this development, seating mainly took the form of stools and benches, and a house would have held at most one armchair, to be occupied by the most important person present (the owner or an honoured guest).

The seat of this chair, beneath the covers, is a fully-formed cushion - a ticking case filled with feathers - which has been nailed down to the frame. This way of forming the seat reveals its development from the use of loose cushions on top of a wooden seat, and marks the beginning of the practice of fixed upholstery.

Design

A square chair, or back-stool, with a deep, square upholstered seat and thinly upholstered low, raked back, raised above the seat, both covered in blue wool with appliqué needlework and space-nailed braid and fringes; on turned front legs and erect, square-section back legs, joined by plain peripheral stretchers close to the ground. The front legs have rings at top and bottom of their turned columns, and are square in section above and below, where they meet the seat rails and stretchers. The legs have been reduced in height and later built up; originally they were probably longer than now.

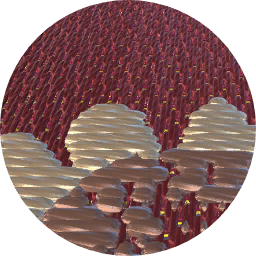

The blue, plain-weave wool is used to cover not only the upholstered pads, but also the seat rails (as extensions of the seat-pad sides), the bottom rail of the inside-back (extending the front back-pad cover), the outside-back, and the struts that raise the back above the seat. These struts are chamfered at each corner (so becoming octagonal in section), and the top rail of the wool-covered back is chamfered along both its top edges. The wool panels, except on the struts, are decorated with appliqué needlework in a design of stylized flowers and leaves entwined around a thin post – with three posts across the width of the chair (on the front, top and back panels, but not on the outside-back), and two between the front and back (on the side panels of the seat).

Needlework and trimmings

The needlework slips applied to the blue wool cover are worked in cross-stitch over two threads of the canvas support, in coloured silk threads. This has mostly disintegrated except on the wool-covered seat rails, and on the back face of the seat pad, but the stitching by which the slips were attached to the wool mostly remains (on the inside-back and the top and sides of the seat), following the same pattern of stylized flowers and leaves entwined around a straight vertical stem as survives on the back of the seat. This scheme is overlaid by the trimmings, of three principal kinds, all in silk: a short fringe, red, green and blue, sewn into the seams of the seat cover; a green and pink striped braid running horizontally under the seat pad (on all four sides) and back pad (on the front face only), fixed with large spaced brass nails; and a yellow and green braid with a long fringe, apparently red, yellow and blue, hanging from the bottom of the seat rails (on all sides) and of the bottom back rail (all around it), its header fixed with small spaced nails. The large and small brass nail-heads (15 and 7 mm in diameter respectively) are aligned with each other (spaced at 25 mm intervals, centre to centre), and on the front of the back pad they both turn the corner and continue, closer together, up the sides. The large brass nails also extend down the front face of the back struts. On the outside-back the small brass nails are used fix the wool to the back struts, as well as to secure the header of the long fringe (the only trimming on the outside-back cover). The same small nails are used to fix a narrow vertical braid to the back and side panels of the seat, at the back corners. This vertical braid appears to be the header to the long fringe, with the fringe cut off or, in places, folded away in the seams. Almost none of the long fringe survives.

Construction

The chair-frame is made of walnut and beech, and is of mortise-and-tenon construction, mostly reinforced with pegs. Walnut is used for the legs and stretchers, except for the back legs, in beech (stained to match the walnut elements), which are integral with the raked uprights of the back-frame. Beech is also used for the rails of the back-frame and the seat rails. The beech in the seat rails and the back right upright is rather low-quality wood, with a large knot in the right upright, another in the left rail, and a waney lower inside edge on the right rail, which is splitting here. The left stretcher also has a pronounced chamfer on the lower inside edge, probably a wane. The other edges of the stretchers and the square-section back uprights are slightly bevelled.

The stretchers are tenoned and pegged, and the seat rails tenoned and double-pegged, to the front legs and the full-height back uprights. The bottom rail of the back is tenoned to the back uprights, which in turn are tenoned to the top rail of the back; whether any of the back-frame joints are pegged is concealed by the upholstery.

Upholstery

The seat upholstery is supported on a foundation of interwoven webbing (two strips in each direction) supporting a base cloth. The webbing, 4.5–5 cm wide, is of plain-weave linen(?), faintly striped, tightly woven and thinner in texture than 18th- or 19th-century webbing. The base cloth is an inconsistent, loosely woven 2/1 twill-weave, of unevenly spun yarns. On top of this foundation is placed a pre-formed ticking cushion case (the bottom panel of which is visible through the base cloth), filled with feathers. It is presumably nailed to the top edges of the seat rails.

The back pad is much thinner and without boxed sides, but is possibly also made as a pre-formed squab. It has a canvas case or base cloth, fixed to the front of the frame, and there is no stuffng in the thickness of the frame, between this pad and the outside-back cover. The covers are fixed with hand-cut iron nails, spaced further apart than the decorative nails and mostly concealed by the braids (but responsive to a magnet).

The chamfering of the top rail, and of the struts between the back and the seat, allows the wool to be pulled tight over these surfaces with less risk of tearing than would be created by right-angled edges.

Condition and repairs

All four feet have been tipped in beneath the stretchers, to a height of about 3.5 cm. This appears to be an old (probably 19th-century) repair, as there are old areas of damage that extend across the joints, notably on the back left leg. On the back right leg is a (still older?) scarfed-in patch, 12.5 cm high at its highest (down to the top of the tipped-in foot). The beech parts of the frame are worm-holed, most densely in the back uprights and the back and left seat rails. The chair-frame has been re-finished with a pigmented wax, giving it an unnaturally dark appearance. This finish may well have been applied by the dealer F. C. Harper, who sold the chair to the Museum in 1912.

The back left upright has been repaired, behind the seat and in the strut above, with two iron plates (responsive to a magnet), on the chamfered back faces. These have been inserted without apparently removing the nails by which the wool cover is fixed to the strut, so they may have been eased in from below. The covers of the seat have been partially unstitched at this corner, perhaps to enable this to happen.

In places modern tacks have been used to re-fix the covers. Some modern tacks also remain in place on the underside of the seat rails and the bottom rail of the back, and on the front face of the back left upright (going into the wool). A fragment of plastic is caught in this last tack, indicating that these were all probably fixings for a 20th-century plastic cover, doubtless fitted at the V&A.

The needlework slips have largely worn out, leaving only traces in the stitching by which they were sewn to the wool covers. They survive in best condition on the back face of the seat pad and the back rail, and in fair condition on the other seat rails, which have had some protection against light from the overhanging seat pad. On the top of the seat pad and the front of the back pad the slips have entirely gone. The chair was described in very similar terms when it was purchased in 1912 (‘from the [covering] the greater part of the appliqué has disappeared’), but comparison with an old photograph shows that it has deteriorated further since then.

There are also several holes in the blue wool cover, chiefly in the main panel of the seat. The ticking cushion case has been painted blue in most of the areas exposed by these holes. A few small areas of more recent loss have not been painted in, for example at the back left corner of the seat, next to the leg, where the ticking is seen in its natural colours.